Il distretto nord della california, 8 settembre 2022, Case 4:22-cv-00422-PJH , Alkutkar c. Bumble, affronta una frequente , ma non per questo poco interessante, fattispecie.

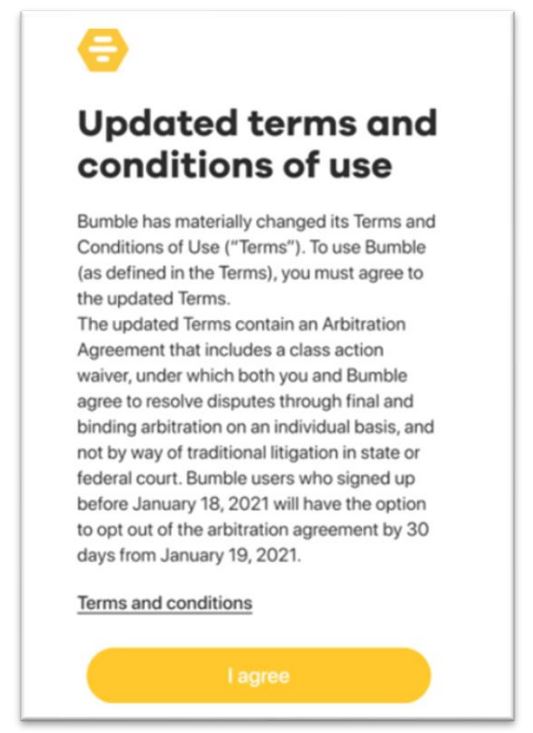

Azionata dall’utente una domanda di inadempiumento verso la piattaforma Bumble (sito di conoscenze e incontri) si vede eccepire la clausola di arbitrato: la quale sarebbe stata approvata in corso di rapporto a seguito di 1) notifica via email e soprattutto 2) di finestra di pop up . -c.d. blocker card- che onerava l’utente di accettar per proseguire . Onere bloccante e finestra che come sempre conteneva un link al nuovo testo del contratto aggiornato, ma che già essa riassumeva la più importante modifica (l’arbitrato appunto).

V. lo screenshot del pop up in sentenza (ma tratto dal blog del prof. Eric Goldman):

Ebbene, per la corte la email (simile al browsewrap) non dà prova di accettazione (p. 11) , ma il pop up con i I AGREE (simile al clickwrap) si.

I dati di Bumble infatti dicono che dopo questo pop up l’utente continuò ad usare i suoi servizi , per cui è presumibile che l’avesse vista e accettata (l’utente lo negava).

Ciò per tre motivi:

1) l’unicità delle credenziali,

2) gli accessi successivi rpesuppongono logicamente/informaticamente accettazione: <<plaintiff’s access and use of the app is a demonstrable consequence of

his assent to the updated Terms. Bumble’s records show that all users were shown the

Blocker Card the first time they signed into the app after January 19, 2021. Wong Decl.

¶ 16 (Dkt. 36-1 at 6-7). The declarations of Bumble’s affiliated engineers make clear that

the Blocker Card functions in a straightforward fashion: it “prevents Bumble users from

accessing or using the Bumble app unless they click on the orange-colored button>>

3) << Lastly, the timeline of events indicates that plaintiff clicked his assent through the

Blocker Card. On January 18, 2021, the Terms governing use of the Bumble app were

updated to include an Arbitration Agreement. Chheena Decl. ¶ 7 (Dkt. 30-1 at 3). On the

same day, the Blocker Card was implemented into the app for existing users, requiring

assent to the updated Terms to access the app the first time a user signed in after

January 18. Chheena Decl. ¶ 11 (Dkt. 30-1 at 3-4); Wong Decl. ¶ 12 (Dkt. 36-1 at 4).

Plaintiff reports that the first time he signed into the app after January 18, 2021, was in

March 2021. Alkutkar Decl., May 14, 2021, ¶ 5 (Dkt. 32-2 at 2). This corresponds neatly

with Bumble’s records, which show that he accessed and used the app on March 4,

2021. Wong Decl. ¶ 18 (Dkt. 36-1 at 7). On that date, plaintiff added new photos to his

profile and swiped on other user profiles, activities that might correspond with a user’s

first time accessing the app following a hiatus. Wong Decl. ¶ 18 (Dkt. 36-1 at 7). Plaintiff

additionally accessed and used the app on March 5, 7, and 11, activities only achievable

following clicking assent on the Blocker Card. Id., ¶ 18. Indeed, plaintiff would not have

been able to purchase the premium features that are the subject of this suit in March,

August, and September 2021 unless he clicked to accept the updated Terms and

Arbitration Agreement. Id., at ¶ 18 >>

In altre più brevi parole <<Bumble has shown that plaintiff used unique credentials to access the app on March 4, 2021, that his access and use of the app on that date was a demonstrable a consequence of his assent to the updated Terms because he only could have done so by clicking through the Blocker Card, and that the timeline of events indicates that plaintiff clicked his assent to the updated Terms. These facts are similar to those found sufficient to authenticate an electronic signature in Ngo, 2018 WL 6618316, at *6, and they are sufficient to authenticate an electronic signature here. Bumble thus establishes by a preponderance of evidence that clicking through the Blocker Card was “the act of” plaintiff necessary to show that he electronically signed and agreed to the updated Terms, including the Arbitration Agreement. >>

(notizia e link alla sentenza dal blog del prof. Eric Goldman)