Eric Goldman dà notizia di NORTHERN DISTRICT Court OF ILLINOIS

EASTERN DIVISION 29 settembre 2023, No. 22-cv-2378, Emoji company v. vari soggetti .

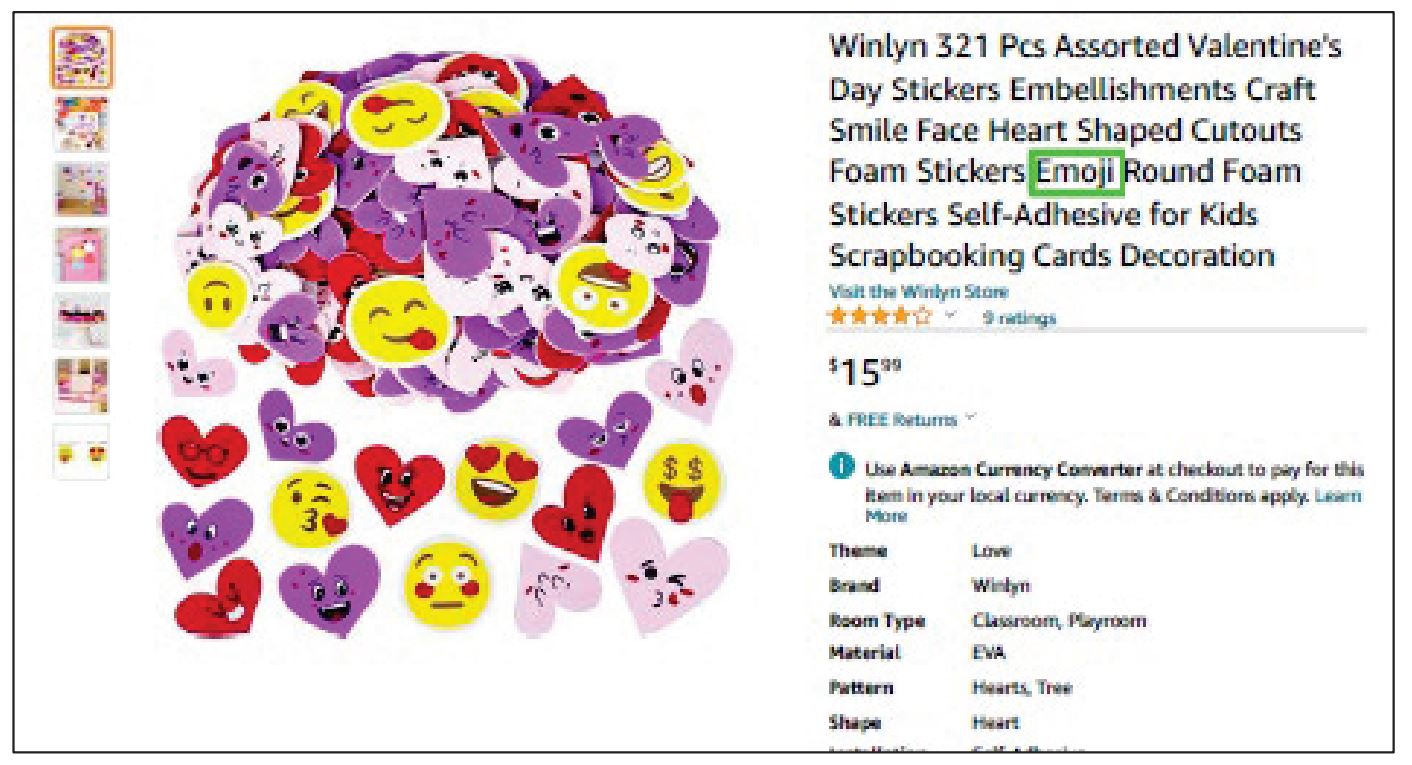

La convenuta aveva usato il marchio denominativo (la parola) “Emoji” nel descrivere i propri prdotti, dato che vendeva stickers che ricordavano la forma di emojis.

Si tratta di fair use secondo il diritto dei marchi usa (da noi art. 21 c.1 c.p.i., xa vedere se lettere b) o c)), dice la corte.

Là è l’argt. 15 US Core § 1115.b. (4): << That the use of the name, term, or device charged to be an infringement is a use, otherwise than as a mark, of the party’s individual name in his own business, or of the individual name of anyone in privity with such party, or of a term or device which is descriptive of and used fairly and in good faith only to describe the goods or services of such party, or their geographic origin;>> (la Corte non menziona la fattispecie sub (4), ma altre paiono non adatte)

Interessante è anche la questione della volgarizzazione del segno.

La corte dice che, impregiudicato se lo sia per digital icons, non lo è per altri prodottio come gli stickers fisici sub iudice: <<But those facts do not strip Emoji Company of trademark protection for the term “emoji”

on classes of products other than digital icons, such as, as relevant here, stickers. That’s because

“emoji” is not a generic term for stickers or emoji-themed stickers. See McCarthy, supra at 12:1

(stating that when a name is generic, “the name of the product answers the question ‘What are

you?’”); see also H.D. Michigan, Inc., 496 F.3d at 760 (“A company’s name may be generic as to

one of its products, but not generic as to its other products, even those related to the first

product. Two Second Circuit decisions illustrate this principle. In one, the court . . . held that the

word ‘safari’ is generic as applied to a type of khaki hat and jacket, but not generic as applied to

boots, shoes, shirts, ice chests, and tobacco. See Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World Inc.,

537 F.2d 4, 11-12 (2d Cir. 1976). In another, the court held that the word ‘self-realization’ is a

generic name for a yoga organization (people performing yoga attempt to attain self-realization),

but descriptive as applied to yoga books and classes. See Self–Realization Fellowship Church v.

Ananda Church of Self–Realization, 59 F.3d 902, 909-10 (9th Cir. 1995).”). Thus, Winlyn has not

shown that Emoji Company has a less-than-likely shot at success on the merits on the basis that its

mark is generic and therefore unprotectable>>.

Questa la pubblicità della covnenuta (su Amazon; immagine rpesa dal blog di Eric Goldman):