Eric Goldman segnala Appello New York 25.11.2024, Wu v. Uber, sull’oggetto, naturalmente sempre sull’approvazione o meno della clausola arbitrale (qui predisposta da Uber).

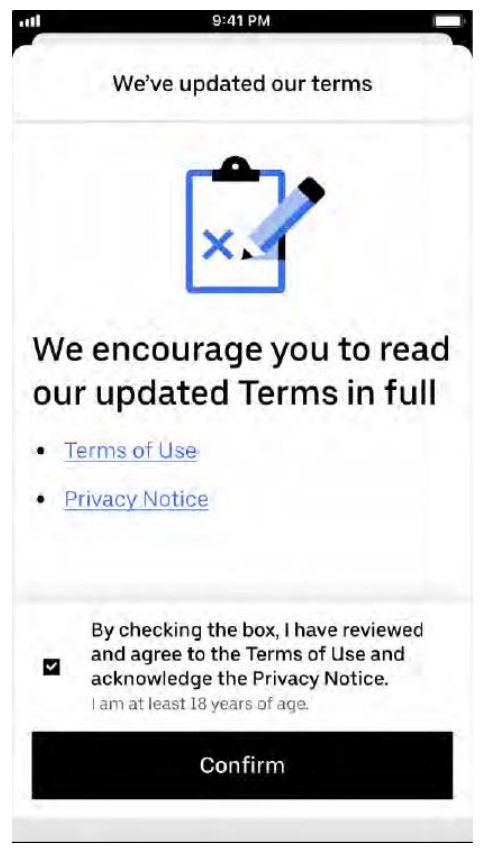

Di seguito lo screenshot rappresentante la modalità richiesta di approvazione:

In generale , dice la corte, non c’è motivo per non applicare la disciplina comune:

<<There is no sound reason why the contract principles described above should not be

applied to web-based contracts in the same manner as they have long been applied to

traditional written contracts. Although this Court has not, until now, had the opportunity

to offer substantial guidance on the question, state and federal courts across the country

have routinely applied “traditional contract formation law” to web-based contracts, and

have further observed that such law “does not vary meaningfully from state to state”

(Edmundson v Klarna, Inc., 85 F4th 695, 702-703 [2d Cir 2023]). Case law from other

jurisdictions may therefore provide useful guidance>>.

Nello specifico, la proposta era sufficientemente chiara:

<< The headline and the larger text in the center of the screen—“We’ve updated our

terms” and “We encourage you to read our updated Terms in full”—clearly advised

plaintiff that she was being asked to agree to a contract with Uber. The terms themselves

were again made accessible by a hyperlink on the words “Terms of Use,” which were

formatted in large, underlined, blue text. A reasonably prudent user would have understood from the color, underlining, and placement of that text, immediately beneath the sentence

“encourag[ing]” users to “read [the] updated Terms in full,” that clicking on the words

“Terms of Use” would permit them to review those terms in their entirety. Finally, Uber

provided plaintiff with an unambiguous means of accepting the terms by including a

checkbox, “Confirm” button, and bolded text expressly stating that, “By checking the box,

I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use.” It is undisputed that plaintiff checked and box and clicked the “confirm” button.>>