Supreme Court US n. 21-869 del 18 maggio 2023, ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, INC. v. GOLDSMITH ET AL. decide l’oggetto.

Decide uno dei temi più importanti del diritto di autore, che assai spesso riguarda opere elaboranti opere precedenti.

Qui riporto il sillabo e per esteso: in sostanza l’esame della SC si appunta solo sul primo elemento dei quattro da conteggiare per decidere sul fair use (In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include : (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; ), 17 US code § 107.

<< The “purpose and character” of AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph in commercially licensing Orange Prince to Condé Nast does not favor AWF’s fair use defense to copyright infringement. Pp. 12–38.

(a)

AWF contends that the Prince Series works are “transformative,”and that the first fair use factor thus weighs in AWF’s favor, because the works convey a different meaning or message than the photograph. But the first fair use factor instead focuses on whether an allegedlyinfringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is amatter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed againstother considerations, like commercialism. Although new expression, meaning, or message may be relevant to whether a copying use has asufficiently distinct purpose or character, it is not, without more, dis-positive of the first factor. Here, the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to infringe her copyright is AWF’s licensing of OrangePrince to Condé Nast. As portraits of Prince used to depict Prince inmagazine stories about Prince, the original photograph and AWF’s copying use of it share substantially the same purpose. Moreover, AWF’s use is of a commercial nature. Even though Orange Prince adds new expression to Goldsmith’s photograph, in the context of the challenged use, the first fair use factor still favors Goldsmith. Pp. 12–27.

(1)

The Copyright Act encourages creativity by granting to the creator of an original work a bundle of rights that includes the rights toreproduce the copyrighted work and to prepare derivative works. 17

U.

S. C. §106. Copyright, however, balances the benefits of incentives to create against the costs of restrictions on copying. This balancingact is reflected in the common-law doctrine of fair use, codified in §107,which provides: “[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching . . . , scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” To determine whether a particular use is “fair,” the statute enumerates four factors to be considered. The factors “set forth general principles, the application of which requires judicial balancing, depending upon relevant circumstances.” Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 U. S. ___, ___.

The first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit

educational purposes,” §107(1), considers the reasons for, and nature of, the copier’s use of an original work. The central question it asks is whether the use “merely supersedes the objects of the original creation . . . (supplanting the original), or instead adds something new, with afurther purpose or different character.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U. S. 569, 579 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted). As most copying has some further purpose and many secondary works add something new, the first factor asks “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original. Ibid. (emphasis added). The larger the difference, the morelikely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use. A use that has a further purpose or different character is said to be “transformative,” but that too is a matter of degree. Ibid. To preserve the copyright owner’s right to prepare derivative works, defined in §101 of the Copyright Act to include “any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed,or adapted,” the degree of transformation required to make “transformative” use of an original work must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative.

The Court’s decision in Campbell is instructive. In holding that parody may be fair use, the Court explained that “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value” because “it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one.” 510 U. S., at 579. The use at issue was 2 Live Crew’s copying of Roy Orbison’s song, “Oh, Pretty Woman,” to create a rap derivative, “Pretty Woman.” 2 Live Crew transformed Orbison’s song by adding new lyrics and musical elements, such that “Pretty Woman” had adifferent message and aesthetic than “Oh, Pretty Woman.” But that did not end the Court’s analysis of the first fair use factor. The Court found it necessary to determine whether 2 Live Crew’s transformationrose to the level of parody, a distinct purpose of commenting on theoriginal or criticizing it. Further distinguishing between parody and satire, the Court explained that “[p]arody needs to mimic an originalto make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s (or collective victims’) imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.” Id., at 580–581. More generally, when “commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, . . . the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger.” Id., at 580.

Campbell illustrates two important points. First, the fact that a use is commercial as opposed to nonprofit is an additional element of the first fair use factor. The commercial nature of a use is relevant, but not dispositive. It is to be weighed against the degree to which the use has a further purpose or different character. Second, the first factor relates to the justification for the use. In a broad sense, a use that has a distinct purpose is justified because it furthers the goal of copyright,namely, to promote the progress of science and the arts, without diminishing the incentive to create. In a narrower sense, a use may be justified because copying is reasonably necessary to achieve the user’s new purpose. Parody, for example, “needs to mimic an original to make its point.” Id., at 580–581. Similarly, other commentary or criticism that targets an original work may have compelling reason to “conjure up” the original by borrowing from it. Id., at 588. An independent justification like this is particularly relevant to assessing fairuse where an original work and copying use share the same or highly similar purposes, or where wide dissemination of a secondary work would otherwise run the risk of substitution for the original or licensedderivatives of it. See, e.g., Google, 593 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 26).

In sum, if an original work and secondary use share the same orhighly similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial, the first fair use factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying. Pp. 13–20.

(2)

The fair use provision, and the first factor in particular, requires an analysis of the specific “use” of a copyrighted work that is alleged to be “an infringement.” §107. The same copying may be fairwhen used for one purpose but not another. See Campbell, 510 U. S., at 585. Here, Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph has been used in multiple ways. The Court limits its analysis to the specific use allegedto be infringing in this case—AWF’s commercial licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast—and expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of the original Prince Series works. In the context of Condé Nast’s special edition magazine commemorating Prince, the purpose of the Orange Prince image is substantially the same as thatof Goldsmith’s original photograph. Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince. The use also is of a commercial nature. Taken together, these two elements counsel against fair use here. Although a use’s transformativeness may outweigh its commercial character, in this case both point in the same direction. That does not mean that all of Warhol’s derivative works, nor all uses of them, give rise to the same fair use analysis. Pp. 20–27.

(b)

AWF contends that the purpose and character of its use of Goldsmith’s photograph weighs in favor of fair use because Warhol’s silkscreen image of the photograph has a different meaning or message. By adding new expression to the photograph, AWF says, Warhol madetransformative use of it. Campbell did describe a transformative use as one that “alter[s] the first [work] with new expression, meaning, or message.” 510 U. S., at 579. But Campbell cannot be read to mean that §107(1) weighs in favor of any use that adds new expression, meaning, or message. Otherwise, “transformative use” would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works, asmany derivative works that “recast, transfor[m] or adap[t]” the original, §101, add new expression of some kind. The meaning of a secondary work, as reasonably can be perceived, should be considered to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original. For example, the Court in Campbell considered the messages of 2 Live Crew’s song to determine whether the song hada parodic purpose. But fair use is an objective inquiry into what a user does with an original work, not an inquiry into the subjective intent of the user, or into the meaning or impression that an art critic or judge draws from a work.

Even granting the District Court’s conclusion that Orange Prince reasonably can be perceived to portray Prince as iconic, whereas Goldsmith’s portrayal is photorealistic, that difference must be evaluatedin the context of the specific use at issue. The purpose of AWF’s recent commercial licensing of Orange Prince was to illustrate a magazine about Prince with a portrait of Prince. Although the purpose could bemore specifically described as illustrating a magazine about Prince with a portrait of Prince, one that portrays Prince somewhat differently from Goldsmith’s photograph (yet has no critical bearing on her photograph), that degree of difference is not enough for the first factor to favor AWF, given the specific context and commercial nature of the use. To hold otherwise might authorize a range of commercial copying of photographs to be used for purposes that are substantially the sameas those of the originals.

AWF asserts another related purpose of Orange Prince, which is tocomment on the “dehumanizing nature” and “effects” of celebrity. No doubt, many of Warhol’s works, and particularly his uses of repeated images, can be perceived as depicting celebrities as commodities. But even if such commentary is perceptible on the cover of Condé Nast’s tribute to “Prince Rogers Nelson, 1958–2016,” on the occasion of the man’s death, the asserted commentary is at Campbell’s lowest ebb: It “has no critical bearing on” Goldsmith’s photograph, thus the commentary’s “claim to fairness in borrowing from” her work “diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish).” Campbell, 510 U. S., at 580. The commercial nature of the use, on the other hand, “loom[s] larger.” Ibid. Like satire that does not target an original work, AWF’s asserted commentary “can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification forthe very act of borrowing.” Id., at 581. Moreover, because AWF’s copying of Goldsmith’s photograph was for a commercial use so similar to the photograph’s typical use, a particularly compelling justification is needed. Copying the photograph because doing so was merely helpfulto convey a new meaning or message is not justification enough. Pp.28–37.

(c) Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, areentitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists. Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original. The use of a copyrighted work may nevertheless be fair if, among other things, the use has a purpose and character that is sufficiently distinct from the original. In this case, however, Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince, and AWF’s copying use of the photograph in an image licensed to a special edition magazine devoted to Prince, share substantially the same commercial purpose. AWF has offered no other persuasive justification for its unauthorized use of thephotograph. While the Court has cautioned that the four statutory fairuse factors may not “be treated in isolation, one from another,” but instead all must be “weighed together, in light of the purposes of copyright,” Campbell, 510 U. S., at 578, here AWF challenges only the Court of Appeals’ determinations on the first fair use factor, and theCourt agrees the first factor favors Goldsmith. P. 38 >>

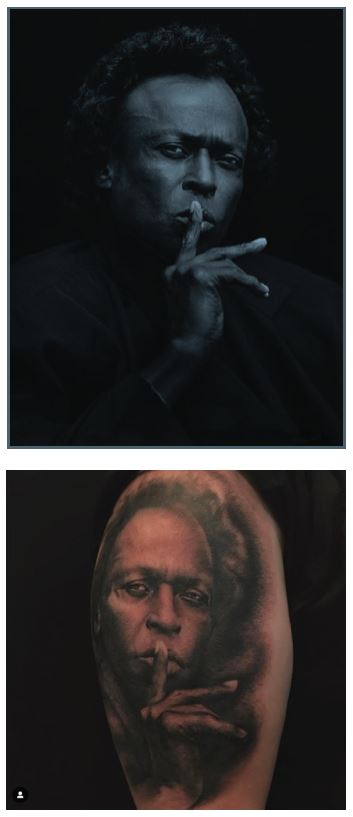

Per quanto elevata la creatività di Wharol, non si può negare che egli si sia appoggiato a quella della fotografa.

Da noi lo sfruttamento dell’opera elaborata, pe quanto creativa questa sia, sempre richiede il consenso del titolare dell’opera base (a meno che il legame tra le due sia evanescente …).

Decisione a maggioranza, con opinione dissenziente di Kagan cui si è unito Roberts. Dissenso assai articolato, basato soprattutto sul ravvisare uso tranformative e sul ridurre l’importanza dello sfruttamento economico da parte di Wharol. Riporto solo questo :

<<Now recall all the ways Warhol, in making a Prince portrait from the Goldsmith photo, “add[ed] something new, with a further purpose or different character”—all the wayshe “alter[ed] the [original work’s] expression, meaning, [and] message.” Ibid. The differences in form and appearance, relating to “composition, presentation, color palette, and media.” 1 App. 227; see supra, at 7–10. The differences in meaning that arose from replacing a realistic—and indeed humanistic—depiction of the performer with an unnatural, disembodied, masklike one. See ibid. The conveyance of new messages about celebrity culture and itspersonal and societal impacts. See ibid. The presence of, in a word, “transformation”—the kind of creative building that copyright exists to encourage. Warhol’s use, to be sure, had a commercial aspect. Like most artists, Warhol did not want to hide his works in a garret; he wanted to sell them.But as Campbell and Google both demonstrate (and as further discussed below), that fact is nothing near the showstopper the majority claims. Remember, the more trans-formative the work, the less commercialism matters. See Campbell, 510 U. S., at 579; supra, at 14; ante, at 18 (acknowledging the point, even while refusing to give it any meaning). The dazzling creativity evident in the Prince portrait might not get Warhol all the way home in the fair-use inquiry; there remain other factors to be considered and possibly weighed against the first one. See supra, at 2, 10,

14. But the “purpose and character of [Warhol’s] use” of the copyrighted work—what he did to the Goldsmith photo, in service of what objects—counts powerfully in his favor. He started with an old photo, but he created a new new thing>>.