Il Tribunale UE 01.09.2021, T-463/20, Sony c. EUIPO, decide una lite su una complessa fattispecie concreta.

Sony fa opposizione alla domanda di marchio denominativo < GT RACING> per prodotti tipo borse etc. a base di cuoio o materiali imitanti il medesimo. Deduce una serie di anteriorità tra cui alcune contenenti l’espressione <gran turismo> e soprattutto una riproduzione delle lettere <GT> con modalità molto stilizzata (al punto da essere con difficoltà leggibili come tali: v. § 5).

Va male a Sony la fase amministrativa e pure il primo grado giurisdizionale con la sentenza de qua.

Interessa qui come viene condotto il giudizio relativo al se una espressione denominativa si confonda con un’espressione grafica molto stilizzata

Premessa (consueta) : <<52. The global assessment of the likelihood of confusion must, so far as concerns the visual, phonetic or conceptual similarity of the signs at issue, be based on the overall impression given by the signs, bearing in mind, in particular, their distinctive and dominant elements. The perception of the marks by the average consumer of the goods or services in question plays a decisive role in the global assessment of that likelihood of confusion. In this regard, the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not engage in an analysis of its various details (see judgment of 12 June 2007, OHIM v Shaker, C‑334/05 P, EU:C:2007:333, paragraph 35 and the case-law cited).

53. According to settled case-law, two marks are similar when, from the point of view of the relevant public, they are at least partially identical as regards one or more relevant aspects (see judgment of 1 March 2016, BrandGroup v OHIM – Brauerei S. Riegele, Inh. Riegele (SPEZOOMIX), T‑557/14, not published, EU:T:2016:116, paragraph 29 and the case-law cited)>>.

Poi:

<<58 In addition, although the marketing circumstances are a relevant factor in the application of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, they are to be taken into account at the stage of the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion and not at that of the assessment of the similarity of the signs at issue. That assessment, which is only one of the stages in the examination of the likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009, involves comparing the signs at issue in order to determine whether those signs are visually, phonetically and conceptually similar. Although that comparison must be based on the overall impression made by those signs on the relevant public, account must nevertheless be taken of the intrinsic qualities of the signs at issue (see, to that effect, judgment of 4 March 2020, EUIPO v Equivalenza Manufactory, C‑328/18 P, EU:C:2020:156, paragraphs 71 and 72 and the case-law cited).

59 Similarly, the reputation of an earlier mark or its particular distinctive character must be taken into consideration for the purposes of assessing the likelihood of confusion, and not for the purposes of assessing the similarity of the marks at issue, which is an assessment made prior to that of the likelihood of confusion (see judgment of 11 December 2014, Coca-Cola v OHIM – Mitico (Master), T‑480/12, EU:T:2014:1062, paragraph 54 and the case-law cited)>>.

Ed eccoci al punto specifico, relativo alla confondibilità tra i segni sub iudice:

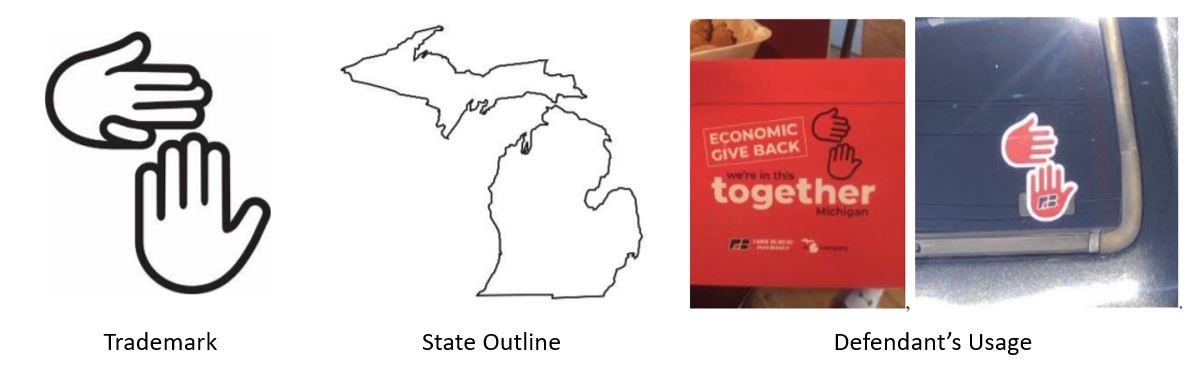

<<66 As stated by the Board of Appeal, the earlier EU figurative mark consists of bold curved, vertical and horizontal lines. It contains a curved vertical line on the left, inclined towards the right, followed by two vertical lines, also inclined towards the right, the first smaller than the second, and a horizontal line which is connected by its lower left corner to the upper right corner of the second vertical line. The mark applied for is the word sign GT RACING, composed of the elements ‘GT’ and ‘RACING’.

67 Contrary to what the applicant claims, the mere fact that the earlier EU figurative mark may have been developed on the basis of the abstract concept of the capital letters ‘G’ and ‘T’ is not in itself a sufficient ground for concluding that there is a visual similarity between the signs at issue, given that the very specific graphic design of that mark has the effect of counteracting to a large extent the alleged point of similarity relating to the fact that it may be understood as a reference to the capital letters ‘G’ and ‘T’ by part of the public.

68 The curved line, the vertical lines and the horizontal line comprising the earlier EU figurative mark are configured in such a way as to refer instead to an almost perfect arrangement of elements resting inside each other or next to each other. They thus provide a highly stylised image. In those circumstances, the consumer would have to engage in a highly imaginative cognitive process in order to ‘decipher’ that figurative sign and to perceive it as representing the capital letters ‘G’ and ‘T’. That close interconnection of the lines comprising that figurative sign will lead the relevant consumer to perceive it as an abstract and unitary shape rather than as the capital letters ‘G’ and ‘T’. As the Board of Appeal correctly pointed out, what is alleged to be the capital letter ‘G’ has neither counter nor chin. What is alleged to be the capital letter ‘T’ does not have a complete arm. The earlier EU figurative mark could also be perceived as the sequences of the upper- and lower-case letters ‘C’, ‘l’ and ‘r’ or ‘E’ and ‘r’ or as the sequence of the upper- and lower-case letters ‘C’ and ‘r’ separated by a full stop>>.