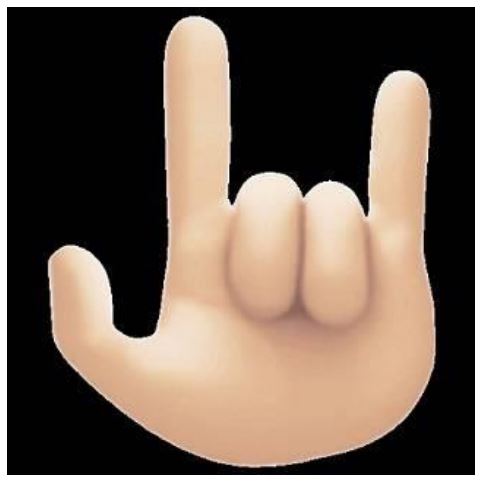

Il 2° board of appeal dell’EUIPO , 1 giugno 2023, Case R 2305/2022-2, Käselow Holding GmbH (qui la pag. web del fascicolo e qui il link diretto al pdf in inglese, traduz. automat. da orig. tedesco), conferma che l’emoji I LOVE YOU nell’ ASL american sign language non è distintivo per servizi finanziari

E’ irrilevante che di solito avvenga con mano destra.

<<22 In general, it should be pointed out that the main function of an emojis is to provide emotional references which are otherwise lacking in tilted entertainment. Emojis therefore function as a parallel language, which convey a nuanced meaning and make it easier to express feelings. They are often connected with positive communication. As a rule, they are not perceived as an indication of origin.

23 This finding is also in line with the case-law, which states that it is sufficient for the finding of a lack of distinctive character if the sign exclusively conveys an abstract promotional statement and is primarily interpreted as an advertising slogan and not as an indication of the origin of the service (05/12/2002, T-130/01, REAL PEOPLE, REAL SOLUTIONS, EU:T:2002:301, § 29-30).

24 It also corresponds to the decision-making practice of the Board, according to which the average consumer is accustomed to a large number of pictograms such as emblems and emojis which represent emotions and are generally used in private communication to express generally positive feelings, such as joy, consent, enthusiasm or happiness. Such pictograms (including emojis) are perceived by the relevant public as a general advertising message or purely decorative elements that are devoid of any distinctive character (see, inter alia, 17/01/2018, R 1489/2017-1, DEVICE OF AN emoji WITH A SMILING FACE (fig.); § 24-26 and 34; 04/10/2013, R 788/2013-4, representation of a smiley, § 13; 16/10/2014, R 602/2014-1, LUBILATED:), § 16-17). The pictograms are often also devoid of distinctive character because they are simple geometric shapes, design elements customary in advertising, stylised instructions on the use of the product or the reproduction of the product itself (29/06/2017, R 2034/2016-4, REPRESENTATION OF ZWEI HÄNDEN (fig.), § 11; 21/03/2006, R 1243/2006-4, Biegsame Welle, § 8; see also 02/04/2020, R 2189/2019-4, REPRESENTATION OF A RED (fig.); 02/10/2017, R 570/2017-4, CIRCULAR FIGURE).

25 In connection with the services claimed, namely financial services (Class 36) and, inter alia, building cleaning (Class 37), the sign in question will therefore be perceived as a general advertising message, which means that customers will be particularly satisfied with the services offered under the sign and will think of them on account of their satisfaction with loved affection.

26 In connection with the services objected to, the consumer therefore merely infers from the sign claimed a positive connotation of a general nature, either in the sense of an attractive decoration, in the sense of a general laudatory statement and incitement to purchase. As a simple representation of a positive gesture, the sign does not contain anything that would enable the targeted consumer to assign the goods thus identified commercially.

27 In summary, it must therefore be stated that the sign is not capable of serving to the public concerned as an indication of the origin of the relevant goods>>.

(notizia e link dal blog del prof. Eric Goldman)