La piattaforma di pagamenti Stripe chiede il consenso al trattamento dati con modalità “sign-in wrap”.

La corte del nord califormia ne esamina (brevemente) la validità ed è per la positiva (US Dis. C. NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 28.07.2021, Case No.4:20–cv–08196–YGR, Silver e altri c. Stripe inc.).

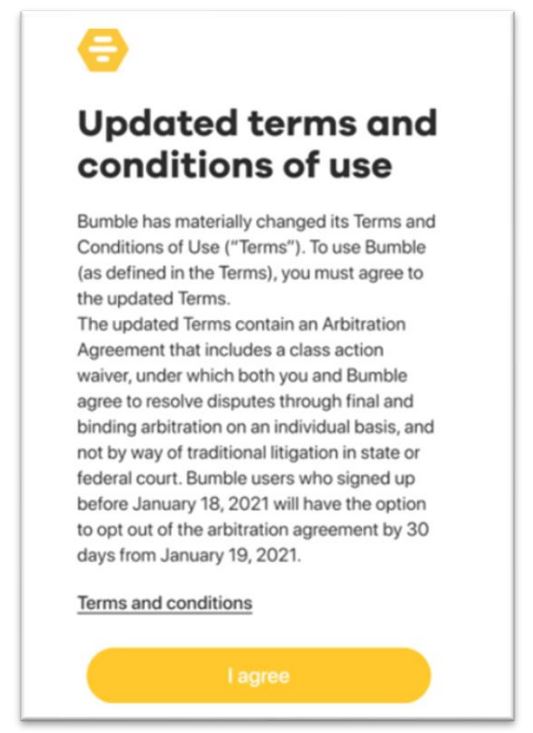

Premessa: << Internet users can form online contract, and therefore consent, in a variety of ways. See Colgate v. JUUL Labs, Inc., 402 F. Supp. 3d 728, 763 (N.D. Cal. 2019) (discussing different forms of online contracts). The Ninth Circuit recognizes three main types of contracts formed on the internet: “clickwrap”, “browsewrap”, and “sign-in wrap” agreements. “Clickwrap” agreements require website users to click on an “I agree” box after they are presented with a list of terms and conditions. Id. “Browsewrap” agreements do not require the express consent, but instead operate by placing a hyperlink with the governing terms and conditions at the bottom of the website. Id. In “browsewrap” agreements, a user gives consent just by using the website. Id. “Sign-in-wrap” agreements are those that present a screen that states that acceptance of a separate agreement is

required before a user can access an internet product or service. Id.

The Ninth Circuit requires that online contracts put a website user on actual or inquiry notice of its terms. Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble Inc., 763 F.3d 1171, 1177 (9th Cir. 2014). In doing so, the notice must be conspicuous, that is it must put “a reasonably prudent user on inquiry notice of the contracts.” Id. Whether a user has such inquiry notice “depends on the design and content of the website and the agreement’s webpage.” Id >>.

Il contratto allora è valido <<if a plaintiff is provided with an opportunity to review the terms of service in the form of a hyperlink,” and it is “sufficient to

require a user to affirmatively accept the terms, even if the terms are not presented on the same page as the acceptance button as long as the user has access to the terms of service.” Moretti v. Hertz Corp., No. C 13–02972 JSW, 2014 WL 1410432, at *2 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 11, 2014); In re Facebook Biometric Info. Priv. Litig., 185 F. Supp. 3d 1155, 1166 (N.D. Cal. 2016) (user agreement enforceable where user had to “take some action— a click of a dual-purpose box— from which assent might be inferred”). >>

Nel caso specifico <<no dispute exists that Instacart utilized a “sign-in wrap” agreement. Instacart’s purchase checkout page required plaintiffs to agree to Instacart’s terms of service and privacy policy whenever they placed an order. Plaintiffs admit that they were presented with the checkout screen as they completed their Instacart orders. (FAC ¶¶ 59, 72, 84, 97, 110.)>>

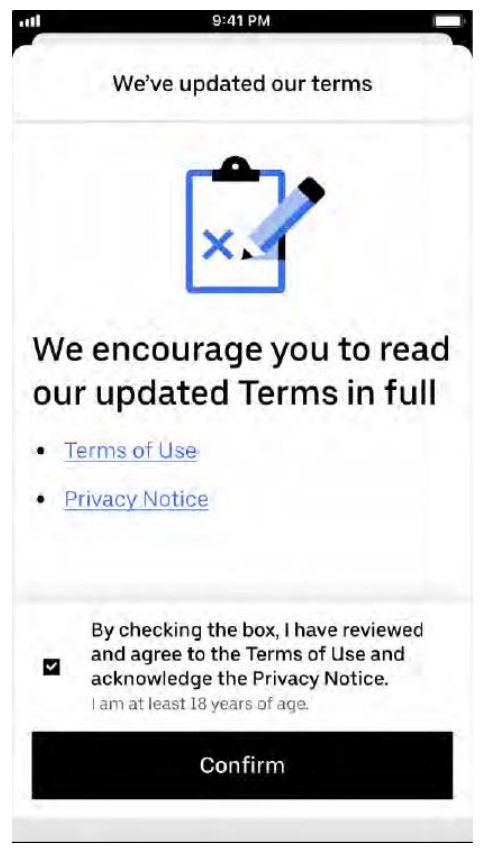

Segue riproduzione di uno screenshot della schermata da cui appare chiaramente che l’intermediario è Stripe (Instacart) : l’acquirente non può allora in buona fede sostenere di aver pensato che l’unico contraente fosse il venditore (anzichè pure Stripe/Instacart).

La cui policy sul punto è allora approvata: << The Court finds Instacart’s privacy policy conspicuous and obvious for several reasons. First, the hyperlink to the privacy policy is displayed in a bright green font against a white background, which stands out from most of the surrounding text. Further, the hyperlink to the

privacy policy is located close to the “place order” button, thus it is hard for a user placing an order to miss it. The bold font alerting consumers to the amount of the charge hold placed on their card calls additional attention to the area where Instacart’s privacy policy is located. There is nothing about the text that makes it inconspicuous or nonobvious.

The Court finds that a reasonably prudent user would have been aware of Instacart’s privacy policy when placing an order. This finding comports with other courts that have found similar “sign-in wrap” agreements to be valid Meyer v. Uber Techs., Inc., 868 F.3d 66, 75-76 (2d. Cir. 2017) (“the existence of the terms was reasonably communicated to the user”) (collecting cases); see also Peter v. DoorDash, Inc., 445 F. Supp. 3d 580, 587 (N.D. Cal. 2020). Based thereon, the Court finds that during checkout, plaintiffs were “provided with an opportunity to review the terms” of the privacy policy. Crawford v. Beachbody, LLC, No. 14cv1583– GPC(KSC), 2014 WL 6606563, at *3 (S.D. Cal. Nov. 5, 2014). They were required to take an affirmative step—clicking the “Place Order” button—to acknowledge that they were agreeing to the terms of the privacy policy. They were told the consequences that would follow from clicking the button, including their acceptance of the privacy policy. Plaintiffs decided to place an order after being made aware of the privacy policy. Accordingly, the Court finds that plaintiffs consented to Instacart’s privacy policy each time they placed an order. In re Facebook Biometric Info. Priv. Litig., 185 F. Supp. 3d at 1166 >>