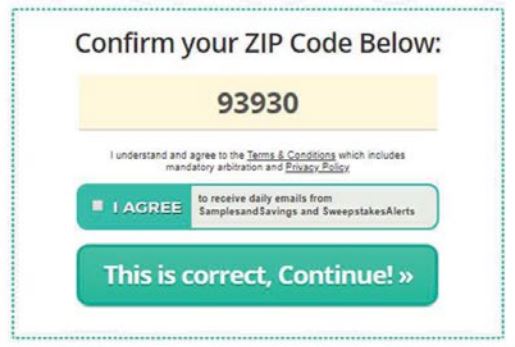

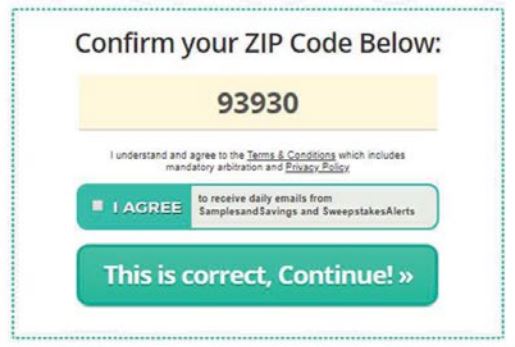

Il 9° circuito conferma una sentenza californiana per cui non è validamente prestato il consenso alla clausola arbitrale , quando l’utente si sia limitato a premere un pulsante I AGREE , preceduto da minuscolo richiamo dal tenore << “I understand and agree to the Terms & Conditions which includes mandatory arbitration and Privacy Policy.” >>.

Si tratta di oggetto del connseso esposto documentalmente in caratteri troppo poco visibili, per cui il connseso non può dirsi validamente formato (manca la reasonably conspicuous notice).

In particolare << The webpages

reproduced in Appendix A and Appendix B did not provide

reasonably conspicuous notice of the terms and conditions

for two reasons. First, to be conspicuous in this context, a

notice must be displayed in a font size and format such that

the court can fairly assume that a reasonably prudent Internet

user would have seen it. See id. at 30; Nguyen, 763 F.3d at 1177. The text disclosing the existence of the terms and

conditions on these websites is the antithesis of conspicuous.

It is printed in a tiny gray font considerably smaller than the

font used in the surrounding website elements, and indeed in

a font so small that it is barely legible to the naked eye. The

comparatively larger font used in all of the surrounding text

naturally directs the user’s attention everywhere else.

And the textual notice is further deemphasized by the overall

design of the webpage, in which other visual elements draw

the user’s attention away from the barely readable critical

text.

Far from meeting the requirement that a webpage must

take steps “to capture the user’s attention and secure her

assent,” the design and content of these webpages draw the

user’s attention away from the most important part of the

page. Nguyen, 763 F.3d at 1178 n.1.

Website users are entitled to assume that important

provisions—such as those that disclose the existence of

proposed contractual terms—will be prominently displayed,

not buried in fine print.

Because “online providers have

complete control over the design of their websites,” Sellers

v. JustAnswer LLC, 289 Cal. Rptr. 3d 1, 16 (Ct. App. 2021),

“the onus must be on website owners to put users on notice

of the terms to which they wish to bind consumers,” Nguyen,

763 F.3d at 1179.

The designer of the webpages at issue here

did not take that obligation to heart.

Second, while it is permissible to disclose terms and

conditions through a hyperlink, the fact that a hyperlink is

present must be readily apparent. Simply underscoring

words or phrases, as in the webpages at issue here, will often

be insufficient to alert a reasonably prudent user that a

clickable link exists. See Sellers, 289 Cal. Rptr. 3d at 29.

Because our inquiry notice standard demands

conspicuousness tailored to the reasonably prudent Internet user, not to the expert user, the design of the hyperlinks must

put such a user on notice of their existence. Nguyen,

763 F.3d at 1177, 1179.

A web designer must do more than simply underscore

the hyperlinked text in order to ensure that it is sufficiently

“set apart” from the surrounding text. Sellers, 289 Cal. Rptr.

3d at 29.

Customary design elements denoting the existence

of a hyperlink include the use of a contrasting font color

(typically blue) and the use of all capital letters, both of

which can alert a user that the particular text differs from

other plain text in that it provides a clickable pathway to

another webpage. See id. (finding “Terms of Service”

insufficiently conspicuous because it did not use all capital

letters or contrasting font color).

Consumers cannot be

required to hover their mouse over otherwise plain-looking

text or aimlessly click on words on a page in an effort to

“ferret out hyperlinks.” Nguyen, 763 F.3d at 1179. The

failure to clearly denote the hyperlinks here fails our

conspicuousness test. Cf. Meyer, 868 F.3d at 78–79 (finding

hyperlinks reasonably conspicuous because they were both

in blue and underlined). >>

Esito condivisibile: e probabilmente non solo per il diritto dei consumatori ma ancbe per il diritto contrattuale generale.

Le due videate contenenti il minuscolo richiamo alle terms and conditiions son questa

e questa

(notizia e link alla sentenza dal post di Venkat Balasubram nel blog del prof. Eric Goldman)