Da molto tempo pende la lite tra Skidmore e i Led Zeppelin.

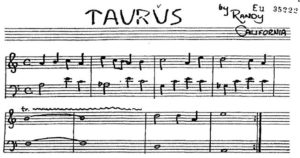

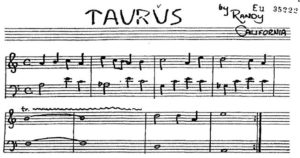

Secondo l’allegazione del primo, rappresentante del Trust Randy Craig Wolfe (creato alla sua morte dalla madre di Randy Wolf, già chitarrista di quel grandissimo gruppo che sono stati gli Spirit: v. voce in Wikipedia), i Led Zeppelin con la canzone Stairway to Heaven avrebbero copiato la canzone Taurus, scritta dal citato Randy Wolfe. Precisamente Skidmore non allega la copia dell’intera composizione Taurus, ma afferma solo <<that the opening notes of Stairway to Heaven are substantially similar to the eight-measure passage at the beginning of the Taurus deposit copy>> (p.10, ove anche precisazioni musicali).:

Decide la lite la United States Court of Appeals del 9° circuito con sentenza (ormai divenuta molto nota) del 9 marzo 2020, processo (docket number) 16-56057.

La prima parte della sentenza riguarda l’individuazione della legge applicabile. Dopo ampia analisi storica, 15 ss, si afferma che questa è il Copyright Act del 1909 e non quello del 1976 e ciò nonostante il primo non proteggesse il sound recording. L’opera sub-judice era stata registrata nel 1967. Per i lavori non pubblicati il copyright è limitato alla deposit copy, che nel caso specifico consisteva di una sola pagina (p.7 e 18; fatti descritti a p. 8/9 ove anche il cenno ai contatti reciproci avuti dalle due band, al fine di provare l’access, su cui v. sotto). A p. 19 ss è esaminata la deposit copy.

La seconda parte della sentenza tratta dei requisiti secondo il diritto statunitense per aversi contraffazione. Sono due (p. 22):

1° l’attore deve aver un valido diritto sull’opera (Taurus, qui);

2° i Led Zeppelin devono aver copiato aspetti protetti dell’opera

Il requisito 2° a sua volta consiste di due componenti autonome:

A) coping

B) unlawful appropriation

Circa A) Poichè la independent creation è un’eccezione totale (complete defense, cioè eccezione che può far rigettare per intero la domanda) , l’attore , se non sa dare prova diretta, può provare il coping in via indiretto/presuntiva, dimostrando i) l’accesso e ii) significative somiglianze : profili che costituiscono il profilo nevralgico della decisione, p. 11-15.

Circa B) , le opere devono avere substantial similarities, p. 23 . Affinchè ciò avvenga, devono essere soddisfatti sia il test estrinseco che il test instrinseco : il primo compara le somiglianze ogggettive di specifici elementi espressivi, il secondo invece valuta <<from the standpoint of the ordinary reasonable observer”, with no expert assistance>>, p.23

Il requisito A (copying e, direi, nella forma del’access) è esaminato a p. 24 ss. Skidmore voleva provare il copying facendo suonare l’opera mentre testimoniava Page: affermava che osservarlo mentre ascolta, avrebbe reso possibile per la giuria capire le sue reazioni e quindi il suo atteggiamento circa la questione dell’accesso. La Corte ritiene non pertinente la prova richiesta, p. 24 (la richiesta era stravagante assai, sia in generale sia in presenza di un consumato uomo di mondo come Page). Il problema dell’accesso però è stato superato radicalmente, poichè Jimmy Page ammise di avere avuto una copia contenente Taurus anche se … negò di conoscere la canzone, p. 25 (cosa per vero sorprendente e in ogni caso interessante giuridicamente: se veramente non l’avesse mai sentita, è dubbio si sarebbe realizzato l’access all’opera, a meno di applicare una presuzione di conoscenza del tipo di quella prevuista per le dichiarazioni recettizie dal nostro art. 1335 c.c.)

Nella parte 4 sono esaminate le istruzioni a suo tempo date alla giuria, che Skidmore contesta.

La più interessante è la prima, circa l’onere probatorio, p. 26 ss

I casi di copyright infringements spesso si riducono alla cruciale questione delle substantial similarities. In passato era opinione diffusa che questo profilo fosse legato a quello dell’accesso, per cui <<“a lower standard of proof of substantial similarity when a high degree of access is shown.” … . That is, “the stronger the evidence of access, the less compelling the similarities between the two works need be in order to give rise to an inference of copying.”>>, p.26

Regola invero poco comprensibile: ed infatti la Corte dichiara espressamente di abrogarla con un overruling , p. 26

Del resto il concetto di accesso non ha più molto senso nel mondo digitale, dice la Corte, visto che < increasingly diluted in our digitali interconnected World>> , p. 31

In ogni caso, nei limiti in cui il concetto di access ha ancora significato , <<the inverse ratio rule unfairly advantages those whose work is most accessible by lowering the standard of proof for similarity. Thus the rule benefits those with highly popular works, like The Office, which are also highly accessible. But nothing in copyright law suggests that a work deserves stronger legal protection simply because it is more popular or owned by better-funded rights holders>>. Infine, la inverse ratio rule <<improperly dictates how the jury should reach its decision. The burden of proof in a civil case is preponderance of the evidence. Yet this judge-made rule could fittingly be called the “inverse burden rule>>, p. 32 (v. anche il prosieguo importante nella seconda parte di p. 32).

Circa la seconda istruzione alla giuria (sull’originalità), la Corte ricorda la giurisprudenza sulla soglia minima di originalità richiesta: in particolare ricorda la notissima sentenza Feist ed altre successive: <<Even in the face of this low threshold, copyright does require at least a modicum of creativity and does not protect every aspect of a work; ideas, concepts, and common elements are excluded….Authors borrow from predecessors’ works to create new ones, so giving exclusive rights to the first author who incorporated an idea, concept, or common element would frustrate the purpose of the copyright law and curtail the creation of new works.>>, p. 33 (e p.38: <<originality requires at least “minimal” or “slight” creativity—a “modicum” of “creative spark”—in addition to independent creation>>).

Poi entra nel merito di teoria musicale, introducendo concetti come chords, arpeggio o broken chord etc.. Infatti l’istruzione contestata diceva: <<that copyright “does not protect ideas, themes or common musical elements, such as descending chromatic scales, arpeggios or short sequences of three notes.>>, p. 35

La terza istruzione riguarda l’omissione di avere dato specifica istruzione alla giuria circa la <selection and arrangement theory>, p. 39 ss e spt. 43 ss: cioè un’istruzione circa la teoria per cui è proteggibile anche un’originale combinazione di elementi di per sè non originali. L’istanza è però respinta per motivi processuali cioè per non averla presentata in modo esplicito e autonomo (dunque con negligenza professionale dei difensori, direi).

E’ vero che Skidmore aveva evidenziato e invocato cinque elementi combinati, ma non li aveva invocati come originalità della combinazione: <<Skidmore and his expert underscored that the presence of these five musical components makes Taurus unique and memorable: Taurus is original, and the presence of these same elements in Stairway to Heaven makes it infringing. This framing is not a selection and arrangement argument. Skidmore never argued how these musical components related to each other to create the overall design, pattern, or synthesis. Skidmore simply presented a garden variety substantial similarity argument.>>, p. 44. In altre parole Skidmore e i suoi esperti <<never argued to the jury that the claimed musical elements cohere to form a holistic musical design. Both Skidmore’s counsel and his expert confirmed the separateness of the five elements by calling them “five categories of similarities.” These disparate categories of unprotectable elements are just “random similarities scattered throughout [the relevant portions of] the works.”>>, p. 45.

Tale istanza dunque va rigettata <<because a copyright plaintiff “d[oes] not make an argument based on the overall selection and sequencing of. . similarities,” if the theory is based on “random similarities scattered throughout the works.”>>, 45/6. Infatti <<presenting a “combination of unprotectable elements” without explaining how these elements are particularly selected and arranged amounts to nothing more than trying to copyright commonplace elements.>>, p. 46. Solo una <<“new combination,” that is the “novel arrangement,” … and not “any combination of unprotectable elements . . . qualifies for copyright protection,”>>, p. 46

La mancanza di elementi originali e proteggibili in Taurus era la tesi centrale della difesa Led Zeppelin (dissenting opinion Ikuta, p. 60)

In sintesi, l’insegnamento sta qui: <<a selection and arrangement copyright is infringed only where the works share, in substantial amounts, the “particular,” i.e., the “same,” combination of unprotectable elements. …..A plaintiff thus cannot establish substantial similarity by reconstituting the copyrighted work as a combination of unprotectable elements and then claiming that those same elements also appear in the defendant’s work, in a different aesthetic context. Because many works of art can be recast as compilations of individually unprotected constituent parts, Skidmore’s theory of combination copyright would deem substantially similar two vastly dissimilar musical compositions, novels, and paintings for sharing some of the same notes, words, or colors. We have already rejected such a test as being at variance with maintaining a vigorous public domain>>, pp. 46/7

A conclusione, la Corte così sintetizza così la propria posizione: <<This copyright case was carefully considered by the district court and the jury. Because the 1909 Copyright Act did not offer protection for sound recordings, Skidmore’s one-page deposit copy defined the scope of the copyright at issue. In line with this holding, the district court did not err in limiting the substantial similarity analysis to the deposit copy or the scope of the testimony on access to Taurus. As it turns out, Skidmore’s complaint on access is moot because the jury found that Led Zeppelin had access to the song. We affirm the district court’s challenged jury instructions. We take the opportunity to reject the inverse ratio rule, under which we have permitted a lower standard of proof of substantial similarity where there is a high degree of access. This formulation is at odds with the copyright statute and we overrule our cases to the contrary. Thus the district court did not err in declining to give an inverse ratio instruction. Nor did the district court err in its formulation of the originality instructions, or in excluding a selection and arrangement instruction. Viewing the jury instructions as a whole, there was no error with respect to the instructions. Finally, we affirm the district court with respect to the remaining trial issues and its denial of attorneys’ fees and costs to Warner/Chappell>> , p. 53 (in italiano, traduzione Google: <<Questo caso sul copyright è stato attentamente valutato dal tribunale distrettuale e dalla giuria. Poiché il Copyright Act del 1909 non offriva protezione per le registrazioni audio, la copia di deposito di una pagina di Skidmore ha definito l’ambito del copyright in questione. In linea con questa azienda, il tribunale distrettuale non ha commesso errori nel limitare la sostanziale analisi di somiglianza con la copia del deposito o la portata della testimonianza sull’accesso al Toro. A quanto pare, la denuncia di Skidmore sull’accesso è discutibile perché la giuria ha scoperto che i Led Zeppelin avevano accesso alla canzone. Affermiamo le contestate istruzioni della giuria del tribunale distrettuale. Cogliamo l’occasione per respingere la regola del rapporto inverso, in base alla quale abbiamo consentito uno standard inferiore di prova di sostanziale somiglianza in presenza di un elevato grado di accesso. Questa formulazione è in contrasto con lo statuto del copyright e noi annulliamo i nostri casi al contrario. Pertanto, il tribunale distrettuale non ha commesso errori nel rifiutare di impartire un’istruzione di rapporto inverso. Né il tribunale distrettuale ha commesso un errore nella sua formulazione delle istruzioni di originalità o nell’escludere un’istruzione di selezione e disposizione. Osservando le istruzioni della giuria nel loro insieme, non si sono verificati errori rispetto alle istruzioni. Infine, affermiamo il tribunale distrettuale per quanto riguarda le rimanenti questioni processuali e la sua negazione delle spese legali e dei costi per Warner / Chappell>>)

Come anticipato, cè una opinione (parzialmente) dissenziente del giudice Ikuta: il dissenso verte soprattutto sulla mancata istruzione data dalla Corte distrettuale circa l’originalità della combinazione di elementi di per sè non originali, scelta confermata dalla maggioranza e contestata da Ikuta, p. 63 ss (per altri profili di dissenso v. 69 ss.)

ora v. la nota anonima alla sentenza in Harvard law review https://harvardlawreview.org/2021/02/skidmore-v-led-zeppelin/